Cannabis Cultivation Facilities: Far UV and UVGI’s Role In Protecting Crop Yields

In the cannabis sector, growers must focus on protecting airstreams and surfaces from unwanted microbes that, if unchecked, can send substantial crop revenues up in a cloud of smoke.

FIGURE 4. Inside this California cultivation facility, ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UV-C) is used in conjunction with an environmental control system to prevent molds and powdery mildew from forming and ruining the crop.

According to the report published by Allied Market Research, the global cannabis market generated $25.7 billion in 2021, and is projected to reach $148.9 billion by 2031, growing at a CAGR of 20.1% from 2022 to 2031. The cannabis market is among the fastest-growing in the United States, Canada, Australia, Denmark, Germany, Thailand, and Uruguay. As the industry shifts from small, unregulated cultivation rooms to larger commercial-scale operations subject to oversight, cannabis production is becoming more sophisticated. Part of this transition involves protecting crops from damaging airborne microorganisms that might proliferate in room air and cause the plants to develop mold and powdery mildew. Not only can such microbes ruin the crop, but they can force the entire facility to shut down due to health violations.

Threats To Cannabis Growth

There are a variety of naturally occurring airborne microorganisms that can cause plants to develop mold or treacherous powdery mildew, rendering cannabis crops, worthless. Standard HVAC systems can actually increase this threat as these damp and dark systems offer a perfect breeding ground for microbial growth. Worse still, ventilation systems are very efficient at spreading microscopic spores throughout a building. Figure 2 shows a breakdown of the most common molds present in indoor air.

Air filtration systems can keep the indoor growing area free of airborne fungal spores. Botrytis cinerea spores (commonly known as gray mold) are approximately 11-12 microns in diameter (Gull 1971), and this size spore will be nearly completely removed by filters rated MERV 12 and higher. Even dust filters of the lowest rating (MERV 6-8) may remove 50% of spores from the air and, with multiple passes (via recirculated air), spores may be completely removed (Kowalski 2006 & 2009). While air filtration provides protection against airborne spores, it has a downside for agricultural production. Humidity levels necessary for cannabis plants to thrive can cause filter media to become damp, encouraging the captured microbes to proliferate.

The Botrytis cinerea spores hail from the outdoors and are brought into indoor cultivation rooms by shoes and clothing. They are also found as common contaminants in about half of indoor environments in the USA, with mean concentrations of about 45-49 CFU/m3 (Shelton 2002).

It is therefore important that cannabis facility workers clean and decontaminate themselves and their smartphones/tablets, watches, wallets, company badges, and keys prior to entering a sterile cultivation environment. Such devices and items can be vectors for pathogens to spread to cannabis plants, which can lead to the growth of powdery mildew. UV-C disinfection devices like Seal Shield’s Electroclave should be deployed at the entrances of all cultivation rooms to avoid such hazards to cannabis crops. Other methods to control Botrytis cinerea include traditional fungicides, but some of these methods may leave hazardous residues that are not suitable for consumption by seriously ill patients (Cervantes 2006). Organic methods are also being studied, including the use of competing or parasitical microorganisms (Wu 2013, Schumacher 2011, Costa 2013). The air quality inside cultivation rooms can also be controlled by deploying upper room UVGI or Far UV lighting either in the 222nm or 254nm wavelength. UVGI or Far UV is the cleanest, most direct way of inactivating dangerous airborne pathogens.

For more info on disinfecting smartphones/tablets, watches, wallets, company badges, and keys via 254nm UV-C with 99.998% efficacy, in just 20 seconds prior to entering a sterile cultivation environment, learn more about Seal Shield’s Electroclave here: https://covspect.com/bio-store/seal-shield

UVGI in Cannabis Facilities

The Far UV or UV-C wavelength (254nm or 222nm) disassociates molecular bonds, which in turn disinfects and disintegrates organic materials, making it an ideal means of permanently inactivating microbes like Botrytis cinerea. In fact, scientists have yet to find a microorganism that’s totally immune to the destructive effects of UV-C, including superbugs and all other antibiotic-resistant microbes. There are two approaches to using UV-C to control mold and bacterial proliferation in indoor cannabis gardens: 1) UV-C airstream disinfection systems and 2) UV-C surface disinfection systems.

222nm Far UV Air and Surface Disinfection for Cannabis

Cannabis cultivators and processors looking to improve terpenes, increase yields, and increase profits should consider deploying 222nm Far UV wands like the Sterilray GermBuster Sabre Far UV Wand. Unlike 254nm, 222nm Far UV is safe for human eye and skin exposure. Far UV light has been shown to have a number of benefits for cannabis plants, including increased terpene production, improved plant growth, and increased yields. One of the key benefits of 222nm Far UV light is its ability to stimulate terpene production in cannabis plants. Terpene production can be increased through short doses of 222nm Far UV light. 222nm Far UV exposure to cannabis plants generates more desirable aromas and flavors, which can be sold by cultivators at a premium price. In addition to increasing terpene production, 222nm Far UV light also promotes plant growth and can increase yields. 222nm Far UV light has been shown to improve plant photosynthesis, leading to larger, healthier plants with more aromatic and desirable bud. 222nm Far UV doses to cannabis result in higher yields for cultivators and processors, which in turn leads to increased profits. Far UV light has a number of benefits for cannabis cultivation and processing, such as reducing the risk of spores, mold, and Powdery Mildew and reducing the need for wasteful and less efficient chemical pesticides. This helps cultivators and processors produce higher-quality cannabis while also reducing operational costs. Overall, deploying 222nm Far UV wands is the most valuable addition to any cannabis cultivation or processing operation looking to improve terpenes, increase yields, and increase profits.

When the USDA initiated 10 years of research on treating Powdery Mildew on Strawberries, the USDA selected Sterilray as their preferred vendor to test the efficacy of their 222nm Far UV disinfection technology. The USDA’s research concluded that, ‘222 nm far UV was three-to ten-fold more effective than 254 nm UV-C in killing conidia of these pathogens, did not require a dark period for enhancing its efficacy, and had no negative effect on plant photosynthesis, pollen germ tube growth and fruit set at doses required to kill these pathogens. The independence from the light conditions most likely spawns from the mechanism of far UV that targets mainly proteins and not DNA as is the case with 254 nm UV-C. Using 222 nm far UV light would allow treatment application at any time of the day as there is no longer the need for a period of darkness as with 254 nm UV-C irradiation. The greater efficacy of 222 nm far UV light treatment will allow UV applicators to travel at increased speeds and cover greater field area making the UV technology even more useful for protecting plants from fungal pathogens.’

222nm far-uvc light for sale - https://covspect.com/bio-store/far-uv-wand

HVAC Surface Cleaning

Surface-cleaning UV-C systems provide 24/7 irradiation of HVACR components to destroy bacteria, viruses, and mold that settle and proliferate on coils, air filters, ducts, and drain pans. UV-C prevents these areas from becoming microbial reservoirs for pathogen growth that will eventually spread into airstreams. They also can provide first pass kill ratios of airborne pathogens of up to 30% with ancillary benefits of restored cleanliness, heat exchange efficiency, and energy use (ASHRAE 2011- Fencl 2013/2014).

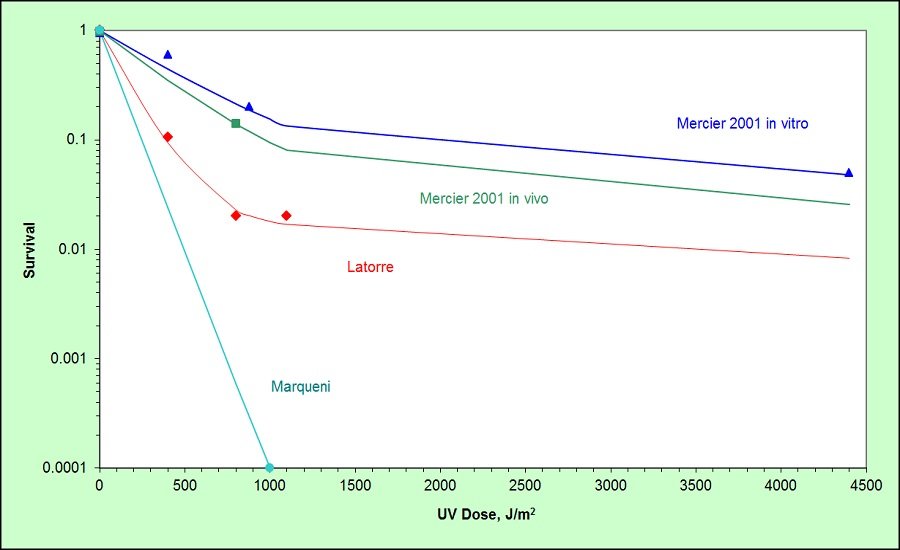

Latorre et al (2012) tested the effectiveness of UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C irradiation on Botrytis cinerea and found UV-C to be the most effective spectrum. The study employed a 20W of UV output. Results indicated zero survival of conidia (spores) at the highest UV dose of 1,100 J/m2.

Mercier et al (2001) used UV-C irradiation in the range of 400-4,500 J/m2 with a 30W of UV output to control the decay caused by Botrytis cinerea on bell peppers. Spore germination was inhibited both in vivo and in vitro, with spore survival rates of 0-5% after a total UV dose of 4,400 J/m2.

Marquenie (2002) irradiated Botrytis cinerea spores using five fluorescent UV lamps of 8W UV output each, and the results show a single stage curve up to the maximum tested dose of 1,000 J/m2. Figure 3 summarizes the results of the three aforementioned tests, which indicate a classic two stage decay curve. The first stage of decay, which is often the most important in disinfection applications, varies from kf = 0.0022 – 0.0093 m2/J. The mean value for the first stage decay constant of Botrytis cinerea is therefore k = 0.0052 m2/J. The range of D90 values, or the dose required for 90% disinfection of spores, is approximately 440-2,000 J/m2. This range of UV susceptibilities compares well with other fungal spores such as Aspergillus or Penicillium (Kowalski 2009).

A critical part in the design of indoor cultivation rooms for medical marijuana is the control of airborne fungal spores, and although most existing facilities are poorly suited to prevent the ingress of fungal spores, they can usually be retrofitted with air filters, fans, and UV systems to render them relatively free of spores. It is important, however, that the facility be airtight and under positive pressure to maintain the high levels of cleanliness necessary to avoid outbreaks of mold. And ideally, every cultivation center should have a pressurized anteroom in which worker access will not cause spores to enter from the outdoors. Operating protocols and regular decontamination are necessary to ensure high levels of cleanliness and disinfection.

Case in Point: Accelerated Growth Solutions

Conor Guckian, a 20-year veteran of HVAC equipment sales, founded Sacramento-based Accelerated Growth Solutions to provide climate and environmental control equipment for the budding cannabis industry.

“Legalization of cannabis has made entrepreneurs more deliberate in the way they design their cultivation facilities,” explains Guckian. “Cultivators are building facilities on a much grander scale, with long-term performance in mind, and are increasingly investing in technologies that will maximize their total yields.”

Guckian’s Accelerated Growth (AG) systems are designed to address these rising demands by regulating temperature, humidity, and vapor pressure differentials to meet the plants’ needs during each step of development.

“Our AG systems modulate to maintain precise temperature and humidity no matter what the load in the space is and, in so doing, provide an environment for plants to flourish,” says Guckian.

One standard, built-in feature in all the AG systems is UV-C germicidal irradiation from Santa Clarita, CA-based UV Resources. The 253.7 nm C-band wavelength inactivates virtually all microorganisms that form on HVACR cooling coils. Left unchecked, these microbes might cause molds and powdery mildew to form, ruining entire crops.

“Placing UV-C lamps directly over the cooling coils is crucial to our ability to maintain a healthy, successful facility,” states Guckian. “An added benefit is the disinfected condensate from the cooling coil that can be recycled for use elsewhere in the facility.”

Alternatives to UV-C include mechanical cleanings, which are often cumbersome and difficult in a crowded facility, or the use of pesticides, which are increasingly avoided by growers due to the hazard they pose to many medical marijuana patients. According to Guckian, UV-C provides the simplest, most efficient means of protecting a cannabis crop from mold.

He points to one cultivation facility based in Desert Hot Springs, CA as an example. The 40,000-sq-ft facility had previously been using stand-alone dehumidifiers, coupled with air conditioners, to control its growing environment. Not only was this existing setup unable to effectively modulate and maintain an ideal growing environment, but the absence of UV-C disinfection meant that mold was always a looming threat.

To improve yields, the facility installed one dozen 35-ton AG environmental units, each serving a 70-light production room. “Installation is incredibly simple,” explains Guckian. “Units are mounted on the floor outside the light room. A small hole is cut in the wall for the return air, and the supply air is released into a fabric duct system.” After seven months of operation, the facility has increased its yields about 60% — from two pounds per light to roughly 3.25 pounds per light. “It’s a relatively inexpensive protection for an incredibly expensive crop,” says Guckian. “You shouldn’t even build a facility without it. It’s not even a question.”

The U.S Department of Federal Agriculture Says Far UV (222nm) is Three-to ten-fold more effective than 254 nm UV-C

The Strawberry cultivation industry, much like the cannabis cultivation industry, suffers from a loss of crops due to Powdery Mildew. Recently developed, night-time irradiation provided the breakthrough that made ultraviolet (UV) technology with 254 nm (UV–C) commercially feasible as a sustainable alternative to synthetic fungicides for control of pre and postharvest diseases of fruit crops. To make UV technology more efficient, The U.S Department of Federal Agriculture explored the effectiveness of far UV (222 nm) produced by a Krypton–Chlorine excimer lamp to kill major fungal pathogens on strawberries such as Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium expansum, and various Colletotrichum species and compared it to the conventional 254 nm UV-C treatment in light and dark. The U.S Department of Federal Agriculture found that 222 nm far UV was three-to ten-fold more effective than 254 nm UV-C in killing conidia of these pathogens, did not require a dark period for enhancing its efficacy, and had no negative effect on plant photosynthesis, pollen germ tube growth, and fruit set at doses required to kill these pathogens. The independence from the light conditions most likely spawns from the mechanism of far UV that targets mainly proteins and not DNA as is the case with 254 nm UV-C. Using 222 nm far UV light would allow treatment application at any time of the day as there is no longer the need for a period of darkness as with 254 nm UV-C irradiation. The greater efficacy of 222 nm far UV light treatment will allow UV applicators to travel at increased speeds and cover a greater field area making the UV technology even more useful for protecting plants from fungal pathogens.

Covspect aims to be the global leader in UV-C and Far UV deployments to the world’s most prominent cannabis cultivators. We ship globally! For UV-C/Far UV product and installation inquiries email sales@covspect.com

Written by Steve Grabenheimer

References;

Borchardt, D. (2017, March 01). “Marijuana Industry Projected To Create More Jobs Than Manufacturing By 2020.” Retrieved September 28, 2017, from https://goo.gl/F51deQ

Boyd-Wilson, K., Perry, J., and Walter, M. (1998). “Persistence and survival of saprophytic fungi antagonistic to Botrytis cinerea on kiwifruit leaves.” Proc of the 51st Conf of the New Zealand Plant Prot Soc, Inc., 96-101.

Cervantes, G. (2006). Marijuana Horticulture: The Indoor/Outdoor Medical Grower’s Guide. Van Patten Publishing.

Cleanlightdirect (2016). “Kill powdery mildew and budrot with UV light.” Clean Light. www.cleanlight.nl.

Costa, L., Rangel, D. E. N., Morandi, M. A. B., and Bettiol, W. (2013). “Effects of UV-B radiation on the antagonistic ability of Clonostachys rosea to Botrytis cinerea on strawberry leaves.” Biological Control 65, 95-100.

Global Cannabis Market to Reach $148.9 Billion by 2031: Allied Market Research https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/09/07/2511824/0/en/Global-Cannabis-Market-to-Reach-148-9-Billion-by-2031-Allied-Market-Research.html

Gull, K., and Trinci, A. P. J. (1971). “Fine Structure of Spore Germination in Botrytis cinerea.” J Gen Microbiol 68, 207-220.

US Department of Agriculture https://pubag.nal.usda.gov/catalog/7471565

Heuvelink, E. (2006). “Reducing Botrytis in greenhouse crops: periodic UV-light treatment in tomato plants.” Wageningen University, Horticultural Production Chains, Wageningen, Netherlands.

Kowalski, W. J., Bahnfleth, W. P., Witham, D. L., Severin, B. F., and Whittam, T. S. (2000). “Mathematical modeling of UVGI for air disinfection.” Quantitative Microbiology 2(3), 249-270.

Kowalski, W. J. (2006). Aerobiological Engineering Handbook: A Guide to Airborne Disease Control Technologies. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Kowalski, W. J. (2009). Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation Handbook: UVGI for Air and Surface Disinfection. Springer, New York.

Latorre, B. A., S. Rojas, G.A. Diaz, H. Chuaqui (2012). “Germicidal effect of UV light on epiphytic fungi isolated from blueberry.” Cien Inv Agr 39(3), 473-480.

Marquenie, D., Lammertyn, J., Geeraerd, A., Soontjens, C., VanImpe, J., Nicolai, B., and Michiels, C. (2002). “Inactivation of conidia of Botrytis cinerea and Monilinia fructigena using UV-C and heat treatment.” Int J Food Microbiol 74, 27-35.

Mercier, J., Baka, M., Reddy, B., Corcuff, R., and Arul, J. (2001). “Shortwave Ultraviolet Irradiation for Control of Decay Caused by Botrytis cinerea in Bell Pepper: Induced Resistance and Germicidal Effects.” J Amer Soc Hort Sci 126(1), 128-133.

Nigro, F., Ippolito, A., and Lima, G. (1998). “Use of UV-C to reduce Botrytis storage rot of table grapes.” Postharvest Biol & Technol 13, 171-181.

Nigro, F., Ippolito, A., Lattanzio, V., DiVenere, D., and Salerno, M. (2000). “Effect of ultraviolet light on postharvest decay of strawberry.” J Plant Path 82(1), 29-37.

Schumacher, J., and Tudzynski, P. (2011). “Morphogenesis and Pathogenicity in Fungi.” Current Genetics 22, 225-241.

By Dr. Wladyslaw Kowalski, Daniel Jones https://www.esmagazine.com/articles/98878-cannabis-cultivation-facilities-uv-cs-role-in-protecting-crops-efficiency

Shelton, B. G., Kirkland, K. H., Flanders, W. D., and Morris, G. K. (2002). “Profiles of Airborne Fungi in Buildings and Outdoor Environments in the United States.” Appl & Environ Microbiol 68(4), 1743-1753.

Wu, Q., Bai, L., Liu, W., Li, Y., Lu, C., Li, Y., Fu, K., Yu, C., and Chen, J. (2013). “Construction of a Streptomyces lydicus A01 transformant with a chit42 gene from Trichoderma harzianum P1 and evaluation of its biocontrol activity against Botrytis cinerea.” Microbial Genetics 51(2), 166-173.